On the 1st of October 2017, the Spanish constitutional disaster in Catalonia got here to a showdown between the independence motion and the central authorities. The confrontation had been within the making since 2010 and geared toward liberation from Madrid. On that day, the Catalan authorities performed a ‘authorized and binding [independence] referendum’ (Deutsche Welle, 2016b), which had been prohibited by the Tribunal Constitucional (TC), the Constitutional Courtroom of Spain. Regardless of this, the vote proceeded and was disrupted by 10,000 Policía Nacional (Nationwide Police Drive) and Guardia Civil (Civil Guard) officers on the orders of the Spanish authorities (BBC, 2017e; March, 2018, pp. 72-86). In the course of the referendum the policemen used power which was instantly branded as police brutality by pro-independence organisations (Òmnium Cultural, 2017), NGOs (Asociación Professional Derechos Humanos de España, 2017), members of the Catalan authorities and supporters (The Guardian, 2017), the worldwide press (BBC, 2017a; BBC, 2017b; La Vanguardia, 2017c), and worldwide politicians (Deutsche Welle, 2017b). All through the subsequent month human rights activist teams, comparable to Human Rights Watch and Amnesty Worldwide, claimed to have collected proof of the mistreatment of residents and concluded that the state forces had used extreme power (Human Rights Watch, 2017; Amnesty Worldwide, 2017b; Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c; Asociación Professional Derechos Humanos de España, 2017).

On account of the referendum the political state of affairs spiralled, Carles Puigdemont[1] and the Catalan authorities declared independence, which in flip prompted the Spanish authorities to invoke article 155 of the structure, thereby eradicating the autonomous privileges of the area (Birke and Kellner, 2017; Ubasart-González, 2021, pp. 48-49). As well as, the Spanish judiciary prosecuted the Catalan independence leaders that had not fled the nation (ibid.; Garcia Valdivia, 2019). Since then, the difficulty has continued to dominate regional politics and frequently flares up nationally, for instance in 2019 when the Catalan politicians had been sentenced, and in early 2021 when the rapper Pablo Hasél[2] was despatched to jail for recidivism (Burgen and Jones, 2019; Congostrina, Bono and Carranco, 2021). Thus, independence stays a up to date and extremely contentious subject.

The intention of this text, nevertheless, is not to analyse the independence subject itself, as so many others have accomplished earlier than, however as a substitute to deal with the occasions of the 1st of October 2017. The central intention is to analyze whether or not or not the federal authorities employed police violence or brutality with a purpose to suppress the vote/the voters. Perplexingly sufficient, the educational group has to this point not performed in depth investigations into the accusation of police brutality. As an alternative, the conclusion drawn by the Human Rights organisations and probably the most outstanding media has prevailed. The consensus is, actually, so dominant, that tutorial articles casually seek advice from “police brutality” of their analysis as if it was an elemental and incontrovertible fact. To call a couple of examples: Cornelis Martin Renes (2019, p. 43): ‘the violent repression of the Catalan referendum’ (my emphasis), Antonio Reyes (2020, p. 486): ‘police brutality in dispersing unarmed residents who aimed to specific their opinions by means of voting’ (my emphasis), and Ignasi Bernat and David Whyte (2020, p. 762): ‘quite a lot of seen cases of state violence’ (my emphasis). The one obtainable tutorial analysis on the subject has been carried out by Núria Pujol-Moix (2019), a professor emeritus of the Autonomous College of Barcelona for medication. Nevertheless, the evaluation was revealed on a non-academic, pro-independence web site, which casts no less than a specific amount of doubt on the impartiality of the investigation. Thus, there isn’t any pre-existing tutorial literature on using power by the state throughout the Catalan independence referendum 2017 as of October 2021. This text goals to rectify the state of affairs by offering scholarly evaluation and understanding the hole between public notion and the prevailing knowledge.

Summarily, this text goals to scrutinise the alleged police brutality throughout the Catalan independence referendum 2017 (abbreviated as 1-O) by contextualising, analysing, and evaluating the obtainable knowledge. Accordingly, the first analysis query is:

Had been the accusations of police violence and brutality throughout the Catalan independence referendum 2017 justified, or did the state make the most of official power throughout an unlawful public meeting? What are the broader implications?

This examine, nevertheless, is not making an attempt to defend any type of police violence or brutality – protesters ought to by no means be mistreated by state forces – as a substitute, this work goals to look at the particular occurrences on the 1st of October 2017 and provide an alternate interpretation.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this investigation. Firstly, and as beforehand talked about, little secondary analysis has been accomplished on the subject, and if in any respect, then focussed on separate however associated points. And whereas these tutorial works present context, they don’t provide examinations on state interference. Thus, this analysis depends largely on major sources comparable to official statements, newspaper articles, NGO studies, and testimonials. Secondly, probably the most critically necessary major supply for this work is in Catalan, not Spanish – nevertheless, it consists primarily of information units and tables, which permits for the interpretation with a dictionary. Nonetheless, it is a potential supply of error, which I’ve tried to counteract with transparency. I’ve included my translations of the publicly obtainable knowledge within the appendix for perusal. Thirdly and eventually, all different sources are both in German, English, or Spanish. Wherever attainable I’ve tried to depend on English sources (for accessibility), nevertheless, the Spanish sources usually provide extra detailed accounts which is why they characteristic closely.

The definition of police brutality

To keep away from any miscommunication or misconceptions, and to protect this analysis’s unequivocalness, exact definitions are decided for the phrases: police power, violence, and brutality. A differentiation between the phrases power and brutality will be present in Lawrence’s “The Politics of Drive Media and the Building of Police Brutality”(2000). She means that the time period power is used for authorized and obligatory violence, whereas pointless power describes a state of affairs the place extreme violence is used unintentionally and with out malice (e.g. officers with inadequate coaching or lack of rational evaluation). Police brutality, alternatively, is disproportionately used power with malevolent intent (Skolnick and Fyfe, 1993, pp. 19-20; Lawrence, 2000, pp. 18-32). One other time period used regularly on this context is pointless or extreme violence, which might be equated with pointless power. These definitions direct using the phrases on this analysis – the referenced sources, nevertheless, would possibly differ from this accord.

Other than the theoretical downside of defining the phrases, the sensible utility of power by regulation enforcement officers presents a a lot graver subject. Recognising, and regulating utilized power closely depends on the circumstances and the person judgment of the officer – in some conditions a verbal immediate is likely to be sufficient to forestall unlawful or harmful conduct, nevertheless, as a rule the officer has to revert to bodily power to restrain an individual and even hearth his gun in self-defence (Alpert and Dunham, 2004, pp. 1-16; Goff et al., 2016, pp. 5-8). This makes it supremely troublesome to supply in depth steering to officers, or states when composing laws, as will be noticed within the official United Nations “Primary Ideas on the Use of Drive and Firearms by Regulation Enforcement Officers”:

‘5. Every time the lawful use of power and firearms is unavoidable, regulation enforcement officers shall:

(a) Train restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the official goal to be achieved;

(b) Decrease injury and harm, and respect and protect human life;

[…]

8. Distinctive circumstances comparable to inner political instability or some other public emergency will not be invoked to justify any departure from these primary rules.

[…]

13. Within the dispersal of assemblies which are illegal however non-violent, regulation enforcement officers shall keep away from using power or, the place that’s not practicable, shall prohibit such power to the minimal extent obligatory.’ (United Nations, 27/08-07/09/1990)

The steering gives the commonest substructure for nationwide laws regarding regulation enforcement, nevertheless, phrases like ‘act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence’ (ibid.) and ‘minimal extent’ (ibid.) are extremely subjective and open to interpretation (Goff et al., 2016, pp. 7-8). Thus, providing very restricted help and steering, which is mirrored by the instruction supplied by NGOs (Amnesty Worldwide, 2015), the European Union (Council of the European Union, 2012; Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, 2001), and nationwide governments. Spanish pointers that had been lively throughout the 1-O embody the “Código Normativo de Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad del Estado”, a regulatory code for state safety forces and our bodies (Ministerio del Inside, 2009), the “Código de la Policía Nacional” (Gobierno de España, 2021a) and the “Código de la Guardia Civil” (Gobierno de España, 2021b). Nevertheless, as already talked about, there may be little steering on the dealing with of using power that exceeds the UN Ideas.

Consequently, this work won’t depend on subjective assessments, however as a substitute, on the publicly obtainable datasets of injured protesters and regulation enforcement officers. Accordingly, this text will take into account either side of the battle, and permit for a data-driven evaluation in an effort to fact-check the hysteria produced by the media, NGOs, and regional in addition to nationwide governments. As soon as once more, this isn’t meant to painting or assess particular person incidents.

The historical past of Catalan independence and the 1-O

Separatism as much as 2017

Catalonia has been part of Spain with plenty of regional id (and push for self-governance) because the 15th century, however after the democratisation of the nation post-fascism within the Nineteen Seventies, it formally acquired a level of regional autonomy (Tortella, 2017, pp. 29-48). Since then, secession had been a minority sentiment, however with the remodelling of the Statute of Autonomy in 2006 and the following attraction towards it the state of affairs modified dramatically (Beltrán de Felipe, 2019, pp. 1-37; Cetrà, 2019, pp. 87-123). The proposed modifications to the Statute included elements such because the elevation of Catalan (the language) above Spanish, the duty to show Catalan in colleges, and essential reforms in fiscal and administrative issues which generated displeasure among the many PP, the Partido Widespread, one of many nationwide events (Beltrán de Felipe, 2019, pp. 8-12; Cetrà, 2019, pp. 87-123). Finally, Mariano Rajoy, the top of the PP and later Prime Minister of Spain, and different members filed an attraction towards the Statute with the Audiencia Nacional de España, the Spanish Nationwide Courtroom. The authorized proceedings lasted till 2010 when the court docket determined that 14 articles of the Statute had been unconstitutional, and 27 wanted additional authorized assessment (Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2010). Primarily, the illegitimate elements had been centred across the minor judicial and monetary elements, however extra prominently across the preferential therapy of Catalan over Spanish. And whereas this resolution affirmed the claims of the PP, it additionally led to widespread protests throughout Catalonia with an estimated attendance of greater than one million individuals in Barcelona alone (Buddy, 2012, pp. 73-107; BBC, 2010; CNN, 2010). Thus, secessionist sentiment grew steadily.

Within the following years, independence from Madrid grew to be the central subject in Catalonia, actually, it developed a lot {that a} coalition between independence events known as Junts pel Sí (JxSí), “Collectively for Sure”, was shaped for the 2015 regional elections (Heller, 2015). The vote was thought-about an indicator of standard opinion and awarded the separatist motion a 48% majority – not an absolute majority – however nonetheless a hit for the pro-independence faction (BBC, 2015). They shaped a coalition, took over the regional authorities, and proclaimed the ‘”inicio del proceso” hacia la independencia’ (‘“starting of the method” in direction of independence’) (Julve, 2015; Noguer, 2015). The central authorities reacted to the initiation by threatening authorized, political, and army motion (Discipline, 2015, pp. 116-136; García, 2016, pp. 229-252; Martí and Cetrà, 2016, pp. 107-119). Thus, the state of affairs in 2016 was fraught with battle when Carles Puigdemont, the newly elected president of the Generalitat, introduced a referendum for the next 12 months (Berwick and Cobos, 2016; March, 2018, pp. 13-18).

October 1st, 2017: the independence referendum

In late 2015 the Spanish nationwide elections failed to supply a authorities, thereby inflicting one other election in June 2016 (Alberola, 2016) with the last word final result of a minority authorities beneath Mariano Rajoy (Jones, 2016; Eldridge, 2021). In the meantime, the secessionist motion had gained momentum and the president of the Catalan Generalitat Carles Puigdemont introduced a legally binding referendum for October 2017 (Deutsche Welle, 2016a; Deutsche Welle, 2016b). Rajoy and the Spanish authorities rejected these assertions and claimed it might do every part in its energy to forestall the secession of any kind (Berwick and Cobos, 2016). In the course of the subsequent seven months, there have been two conferences with representatives of either side, nevertheless, neither resulted in a compromise (March, 2018, p. 17). The state of affairs worsened when the date for the referendum was introduced on the 9th of June and the Catalan parliament began passing laws to facilitate it (ibid., pp. 19, 45-46; Jones, 2017a).

Within the months earlier than October, Catalonia handed political and authorized proceedings to accommodate the vote strategically. For instance, the invoice for the referendum was logged with parliament on the 31st of July, the final day earlier than the summer season recess, leaving no time for dialogue (March, 2018, p. 55). Furthermore, on the 6th of September, it was then abruptly launched within the plenum, and beneath authorized modifications, itwas ratified (Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a; Puente, 2017b). The regulation established the authorized framework for the referendum however was suspended ‘on a precautionary foundation’ (Tribunal Constitucional, 2017) by way of the attraction of the Spanish authorities to the TC on the subsequent day (ibid.; Pérez, 2017; Cortizo, 2017a).

Along with the authorized prohibition, the central authorities made each effort to dam the vote. Thus, the unique plan of utilizing public funds – offered by the central authorities – for the referendum, was thwarted by the Public Prosecutors Workplace after they requested the Generalitat to pay bail of greater than 6 million euros to forestall misuse (Parera, 2017; 20 Minutos Editora, 2017; Marraco, 2017). Madrid and the Public Prosecutors Workplace additionally ordered the seizure of voting supplies comparable to poll bins, voting papers, voting station manuals, and so on. (Navarro, 2017; Europa Press, 2017b) and the closure of all governmentally run webpages promoting or providing directions for the vote (El Diario, 2017a). Total, the seizure of the supplies concluded in an unsatisfactory method, because the vote went forward with sufficient supplies (El Mundo, 2017; El Nacional, 2017; El Confidencial, 2017; Marín, 2017; Público, 2017; Zuloaga, 2017). The repression of on-line communication in regards to the referendum was equally unsuccessful because the pro-independence leaders and organisations had been supported by Russian hackers (Alandete, Dolz, and Busquets, 2017; El Diario, 2017a). Other than these efforts, conventional media and regional politicians had been dissuaded from aiding the vote which resulted in a number of municipalities cancelling pro-independence occasions and rallies (Bandera, 2017; La Vanguardia, 2017b). The suppression of details about the referendum was then topped by the operations Anubis and Copernicus, the primary one facilitating the arrest of political actors that had been actively organising the referendum (Arroyo, 2017; El Diario, 2017b) and the second deployed 10,000 Nationwide Police and Civil Guard officers to Catalonia previous to the referendum (BBC, 2017e; March, 2018, pp. 72-86). Thus, the Spanish authorities had exhausted each authorized and political avenue to hinder the vote and ready to make use of power, which was massively criticised (Altimira, 2017; Cortizo, 2017b; Letamendia, 2018).

The organisation of the referendum itself relied on volunteers who hid and transported polling supplies, in addition to manned the voting stations. Since every part was carried out secretly, plenty of the supplies arrived simply in time on the day earlier than the referendum. The polling stations had been arrange within the early morning surrounded by cheering crowds and solely sometimes hindered by the Mossos d’Esquadra, the regional police power (which largely abstained from interfering throughout the voting) (Berwick and Dowsett, 2017), the Nationwide Police, and the Civil Guard (Sallés, 2017). Polling stations had been ready from 8 a.m. onwards, opened at 9 a.m., and closed at 8 p. m. (Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017b, p. 4; Congostrina, 2017). Over the course of the day, the Policía Nacional closed 46 polling stations, and the Guardia Civil one other 46 with a complete of twelve injured state officers reported by the Ministry of Inside on the night time of the 1st of October (Ministerio del Inside, 2017). Nevertheless, the quantity dramatically elevated over the subsequent 24 hours, first to 39 and on Monday to 431 – the Ministry of Inside defined that cops with any type of harm (bruises, scratches, and so on.) had been now counted too (La Vanguardia, 2017d). The sudden rise in accidents was attributed to the statistics launched by the Catalan Well being Division, which initially reported 844 injured individuals, however later corrected the quantity to 1,066 (Iglesias, 2017; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017b; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018). Spanish media accused either side, however particularly the Catalan officers, of inflating the numbers, for instance, with nervousness assaults of people that had not even been current throughout the voting (Congostrina, 2017; El País, 2017b). A supervisor of the hospital system in Catalonia, who stays nameless in Iglesias’ article, expressed that ‘los números se han inflado’ (‘the numbers had been inflated’) (2017).

Madrid, alternatively, was closely criticised for utilizing extreme power, some information shops and politicians even denounced it as police brutality (BBC, 2017a; BBC, 2017b; The Guardian, 2017; Deutsche Welle, 2017a). The photographs on social media provoked outrage among the many Spanish and worldwide viewers, which known as for the suspension of the motion (Congostrina, 2017). Politicians and worldwide organisations round Europe demanded the tip of the police violence on the day and condemned it within the following days (Council of Europe, 2017; Deutsche Welle, 2017b; El Diario, 2017c; Minder and Barry, 2017). In reality, Greg Russell claims that the German chancellor Angela Merkel interfered on the behalf of the Catalans (2018) to finish the motion early, and whereas there isn’t any official supply to corroborate the allegation, another media shops and organisations affirm a untimely finish of the police intervention (Greenfield, Russell, and Slawson, 2017; López-Fonseca, 2017a). In accordance with these articles, the state forces retreated between 1-2 p. m., hours earlier than the tip of voting.

The end result of the referendum was introduced throughout the night time and, as predicted, confirmed an awesome majority in favour of independence. 2,262,424 individuals voted – roughly 42% of the voters (5.3 million) – nevertheless, allegedly about 770,000 votes went lacking because of the state interruptions in response to officers (Greenfield, Russell, and Slawson, 2017). In whole, the yes-ballots amounted to 90%, therefore giving Catalonia the best to secede beneath the stipulations of the suspended Referendum Regulation (El Plural, 2017; Minder and Barry, 2017). 5 days later, on Friday the 6th of October, the results of the vote was formally introduced to the Catalan parliament, which counted extra 23,793 ballots, and confirmed the turnout of 43%, with 90% pro-independence and eight% towards (Puente, 2017a; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a).

The outcomes of the referendum had been subsequently contested[3], and unsurprisingly not accepted by the Madrid authorities (Gobierno de España, 2017). Within the aftermath, Carles Puigdemont declared independence however suspended the declaration instantly with a purpose to open up the dialogue with Rajoy (BBC, 2017d; La Vanguardia, 2017e). The next confusion over the declaration led the Prime Minister of Spain to declare an ultimatum on whether or not or not Catalonia had declared independence (Minder, 2017b; Jones, 2017b), however when it expired with out a clear reply from Barcelona, he requested the Senate to approve the appliance of article 155 of the structure with a purpose to droop the regional autonomy (Díez and Mateo, 2017; Gobierno de España, 2016). In response to that, the Catalan authorities issued a declaration of independence on the 27th of October, the identical day that Mariano Rajoy’s request for the implementation of article 155 was authorized. Thereupon the Catalan parliament was dissolved, regional elections had been known as, and a number of other politicians fled the nation (Parlament de Catalunya, 2017; Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2017a; Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2017b; Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2017c; Castro and Ponce de Léon, 2017). The remainder of the regional authorities was summoned to court docket, trialled, after which sentenced on the grounds of sedition and misuse of public funds (Garcia Valdivia, 2019). The ruling induced protests, particularly within the streets of Barcelona, however general, it was the ultimate nail within the coffin for the 2017 referendum, albeit not for the independence motion (Burgen and Jones, 2019).

The allegations of police violence and brutality throughout the referendum unfold internationally in a matter of hours. Nevertheless, within the aftermath, contradictory proof emerged. Allegedly, a number of of the photographs, movies, and tales that sparked worldwide outrage had been both exaggerated or from different incidents (ABC Cataluña, 2017; Confilegal, 2017; Libertad Digital, 2017; Preston, 2017). As well as, the accusation of inflation of the statistics of the injured individuals, officers, and protesters alike, surfaced (BBC, 2017c; Iglesias, 2017).

Regardless of these contradictions, two extremely influential human rights organisations, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty Worldwide, revealed studies on the referendum supporting the allegations of the extreme police power (Amnesty Worldwide, 2017b; Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c; Human Rights Watch, 2017). Amnesty Worldwide reported on polling stations in Barcelona (Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c), whereas Human Rights Watch investigated in Girona, Aigneviva, and Fonollosa (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Each concluded that extreme use of power by the police occurred. Along with the accusations of police violence, intimidation of journalists has additionally been identified by Reporters With out Borders and newspapers (Amnesty Worldwide, 2017a; Gálvez, 2017; La Vanguardia, 2017a; Reporters With out Borders, 2017a; Reporters With out Borders, 2017b). The allegations led to judicial proceedings, however the difficulties of identification of perpetrators and inadequate proof usually resulted in dismissal (Confilegal, 2017; Libertad Digital, 2017). Total, Libertad Digital argues that the state forces obtained away calmly and that in actuality, the variety of injured civilians was at about 130 – a far cry from the preliminary 844 (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017b) and the later reported 1,066 injured individuals (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017c; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018).

Statistical evaluation of the state interference

As described above was the state of affairs earlier than, throughout, and after the referendum – plenty of allegations from all sides. For a rational, factual, and demanding evaluation of the state-used power, the official statistics (revealed by the Catalan Generalitat and the Spanish authorities) have to be evaluated and put into context on a numerical degree. Antecedently, two primary disclaimers need to be elaborated. Firstly, that is foremost a statistical evaluation, it isn’t an appraisal of particular person incidents. The end result, due to this fact, displays the typical occurrences (or non-occurrences). Secondly, at greatest, the obtainable knowledge is non-transparent and obscure, attributable to altering figures, allegations of manipulation, and exaggeration, along with the unverifiability of the proof. Due to this fact, this evaluation will deal with the widespread development that manifests regardless of these limitations.

Proportion of inhabitants/voters/injured individuals

Catalonia accounts for 16% of Spain’s inhabitants and was quantified at roughly 7.5 million in 2017 (Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya, 2020). From that inhabitants about 5.3 million individuals had been eligible to vote within the referendum of which 2.3 million submitted a legitimate poll (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a) – moreover, officers claimed that circa 770,000 ballots went unaccounted for because of the police intervention (Greenfield, Russell, and Slawson, 2017). This discrepancy of a fourth of the ballots would affect the statistical concerns closely, nevertheless, probably the most verifiable and solely official quantity data 2.3 million votes[4]. It’s due to this fact used because the baseline for all following statistical concerns.

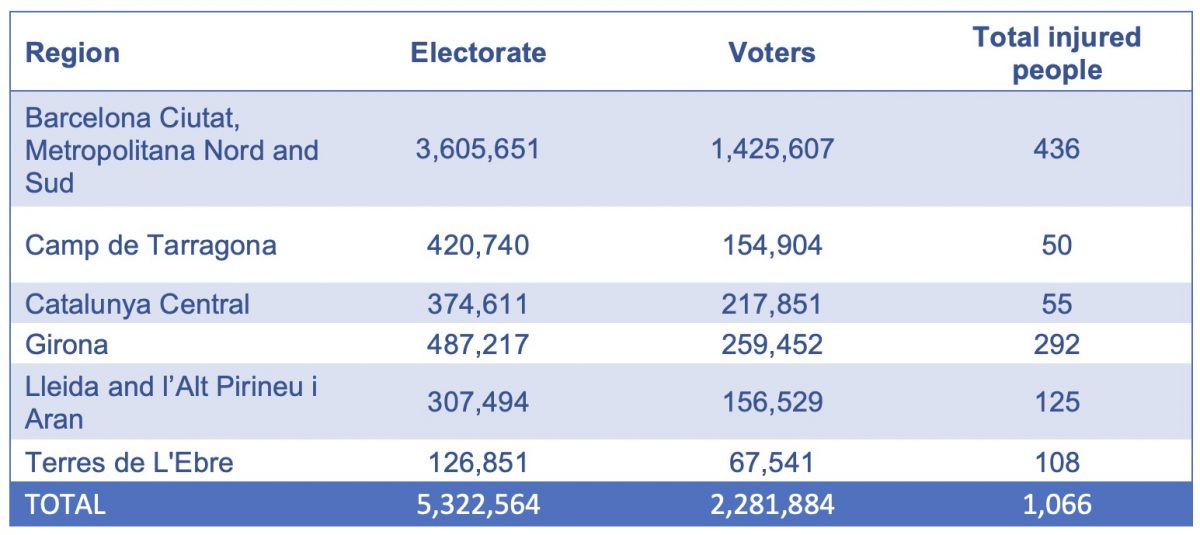

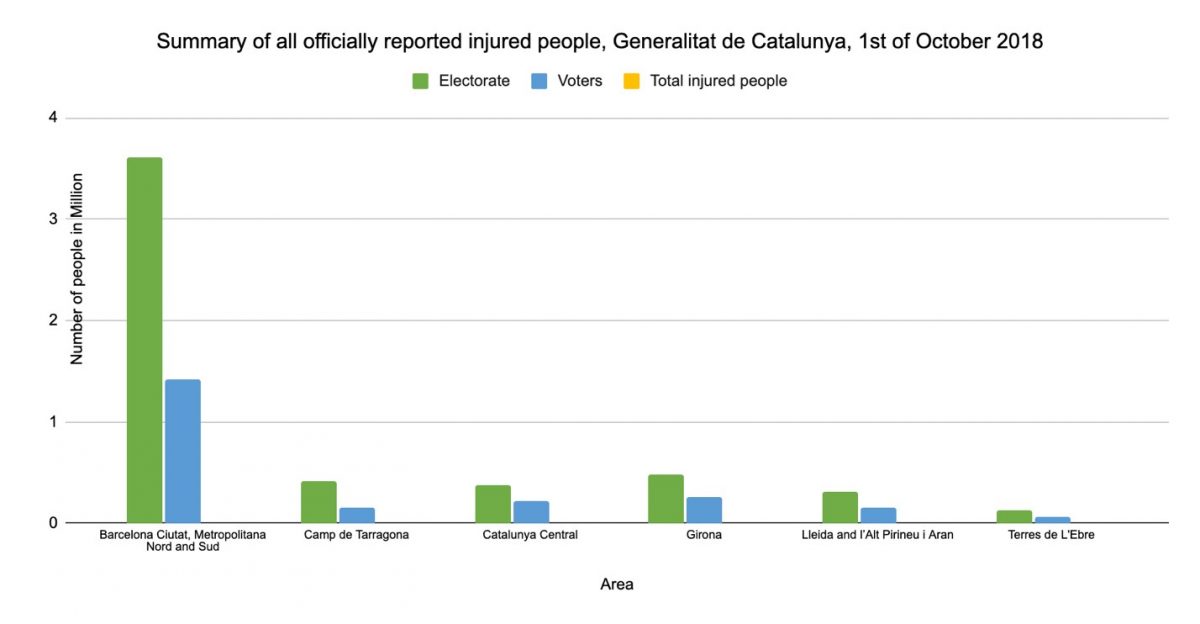

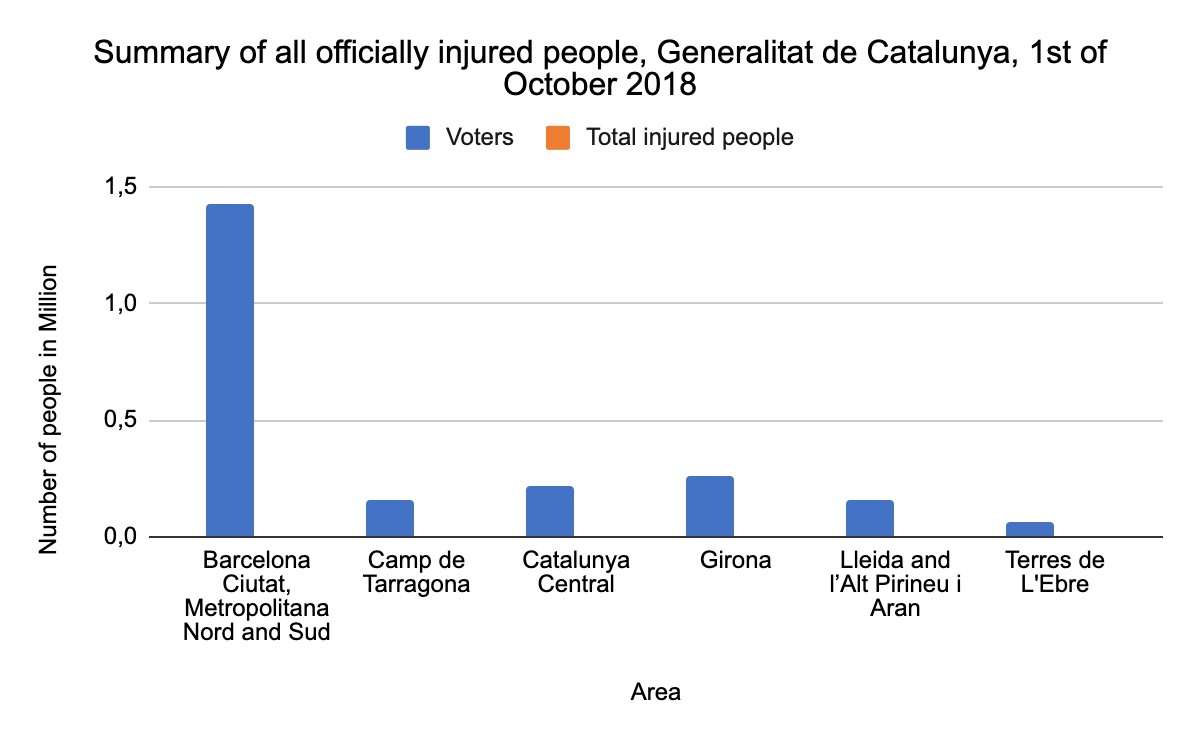

As will be seen in Figures 1 and a couple of the relative variety of injured individuals to the voters is minuscule. Disregarding the entire voters, the overall of injured individuals to voters nonetheless contains a tiny minority (Determine 3). The next desk (Determine 4) reveals this with extra readability, lower than 0.05% of the residents that voted reported accidents. Unquestionably, each harm to a peaceable protester is a person injustice, nevertheless, these statistics indicate that both the alleged police violence and brutality should have occurred in confined incidents since far lower than 1% sought medical assist, or it didn’t happen within the breadth generally assumed. The accusations of widespread police brutality are actually diametrically against the right here offered proof.

The reported severity of the accidents

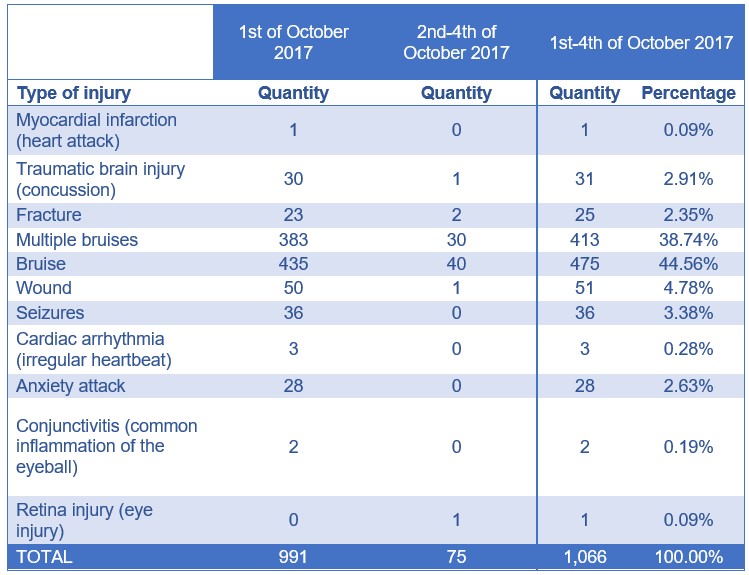

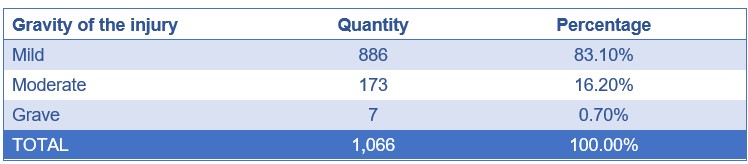

On the matter of harm severity, a report known as “Primer d’Octubre” was revealed by the Catalan Generalitat on the 1st of October 2018, which listed the harm varieties and gravities. Determine 5 summarises these accidents in a desk in English, whereas Determine 6 compiles the levels of severity within the reported accidents from the identical supply. The desk in Determine 5 reveals that almost all of the accidents fall within the classes of bruises, actually, they make up 83.3% of them. This excessive share implies that “little” power was used towards the voters and protesters, thereby undermining the claims of police brutality. Determine 6 studies on the gravity in three classes: gentle, reasonable, and grave – with few individuals being reasonably or gravely injured (lower than 17%). On the account of those numbers, it turns into clear that most individuals suffered no or gentle accidents. Comparatively, lower than 1% of all injured individuals endured extreme hurt and the information gives no specification on how individuals obtained their accidents and whether or not they had been brought on by the police straight, not directly, or in no way.

Total, this report by the Generalitat highlights the low variety of main accidents, thereby contradicting the claims of widespread police brutality additional. Police violence alternatively is much less extreme and can’t be challenged as a lot with the supplied knowledge, however the overarching implication of little utilized power towards civilians prevails. Moreover, it also needs to be famous that the Generalitat solely revealed the great statistics a 12 months after the incidents occurred, thereby limiting and even obstructing the verifiability of the report. Thus, the validity will be questioned and the numbers in relation to the broader image current a distinct story than the media or the Catalan authorities on the time.

Comparability of police presence throughout 1-O and El Clásico in 2019

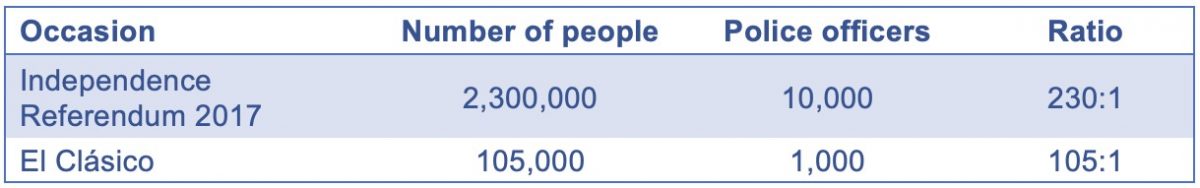

Along with the reported numbers of injured individuals, an evaluation of the ratio between civilians and cops will be made. A number of sources confirmed that circa 10,000 Nationwide Police and Civil Guard officers had been despatched to Catalonia in anticipation of the referendum (BBC, 2017e; March, 2018, pp. 72-86). The Mossos d’Esquadra, which has about 17,000 officers (Mossos d’Esquadra, 2021), introduced previous to the voting day that they might solely cease public unrest (López-Fonseca, 2017b; Minder, 2017a). They refused to close down polling stations, abstained from interfering, and in the end solely noticed the voting (Berwick and Dowsett, 2017).

Ergo, on the time of voting, there have been 10,000 cops able to intervene. To estimate whether or not the police presence was proportionate to the occasion, it will likely be in comparison with the safety presence throughout the soccer recreation: El Clásico. Often, the sport between Barcelona FC and Actual Madrid attracts massive crowds, however in 2019 it was moved attributable to huge protests after the sentencing of the Catalan independence leaders. When the match passed off months later, extra police forces had been despatched to supervise it. Barcelona’s stadium accommodates roughly 100,000 individuals and in 2019 1,000 cops plus a further 2,000 stadium stewards had been employed for security (Lowe, 2019). Official police sources say that along with the stadium viewers about 5,000 individuals protested within the streets (Keely, 2019), which adjusts the ratio for El Clásico to 105:1 protesters/officers (solely counting the official cops) in Determine 7. As compared, the ratio was 230:1 on the day of the referendum. Regardless of the modification for El Clásico, the discrepancy between the police presence at each occasions is extraordinarily important, with greater than a doubled ratio of officers for the soccer recreation. As well as, this comparability solely considers the legitimate votes that had been reported, however the variety of individuals on the road on the 1st of October 2017 might have been considerably larger. Quite the opposite, it could possibly be argued that lots of the voters forged their poll after which left because of the police presence – the precise variety of common current individuals might due to this fact fluctuate dramatically, which is why the poll quantity is assumed as probably the most rational and believable quantity. Regardless of these concerns, the ratio between cops and voters stays in disfavour for the police forces and signifies that they had been severely outnumbered, no less than on the peak of the confrontation on the 1-O.

Contemplating the agitation and battle that surrounds the topic and prior incidents would enable for the affordable assumption that the Spanish authorities ought to have been conscious of the potential, however nonetheless despatched inadequate numbers of officers. So why did they? The Nationwide Police has about 70,000 officers, whereas the Guardia Civil has roughly 80,000 staff (López-Fonseca, 2020), which, if all officers had been despatched, would have diminished the ratio to fifteen:1 – an absence of police power was due to this fact not the explanation. Sending all of them, nevertheless, wouldn’t have been sensible, however even an elevated quantity would have offered reduction and presumably prevented the referendum, however they didn’t. Thus, the choice to solely ship 10,000 officers has two attainable explanations: both they anticipated much less hassle, or it was a deliberate resolution. Maybe it’s attainable that the police power was not despatched to forestall the referendum, however to current a possible objection to it, in order that the central authorities might oppose the end result on extra grounds, however on the identical time couldn’t be accused of army suppression of public opinion.

Contrasting police intervention and non-intervention

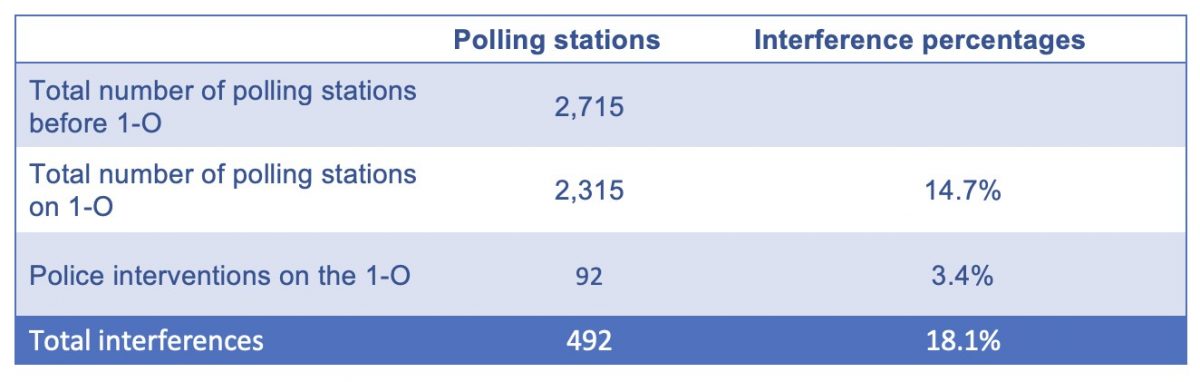

To additional the earlier level, one other side have to be examined: the restraint of the police intervention. Total, Catalonia had 2,315 polling stations on the day of the referendum and in response to the official assertion of the Ministry of Inside, solely 92 of them skilled police intervention (Güell, 2017; March, 2018, p. 88; Ministerio del Inside, 2017). An extra 400 reportedly had been shut down beforehand and therefore recorded no ballots (El Plural, 2017). Determine 8 summarises the interferences earlier than and throughout the referendum – the 400 polling stations that had been closed previous to the referendum are displayed, however since they weren’t closed on the day of the referendum, there isn’t any hyperlink to the police brutality allegations on 1-O. Total, the desk reveals that there was little police interference, since lower than 4% of the polling stations had been both closed or the ballots seized.

These statistics mixed with the findings from the comparability of police presence throughout El Clásico and the referendum recommend a really restricted extent of police presence and interferences. Additional help for this evaluation comes from the accounts of the early dissipation of the police motion on the 1st of October – some sources declare as early as 2 P.M. (Greenfield, Russell, and Slawson, 2017; López-Fonseca, 2017a). The accuracy of those claims is contested since they don’t seem to be talked about within the official announcement (Ministerio del Inside, 2017) and Human Rights Watch dates one police intervention in Aiguaviva at round 4 P.M. (Human Rights Watch, 2017). However the overarching implication stays: few cops took little motion.

Evaluating the proof introduced by human rights organisations

Regardless of these quantitative discrepancies between the media portrayal and the confirmed numbers, two extremely influential human rights organisations, Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty Worldwide, revealed studies on the referendum supporting the allegations of extreme police violence (Amnesty Worldwide, 2017b; Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c; Human Rights Watch, 2017). 5 observers of Amnesty Worldwide reported on polling stations in Barcelona (Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c), whereas Human Rights Watch investigated throughout and after the referendum within the native cities of Girona, Aigneviva, and Fonollosa (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Each organisations declare to have witnessed proof of the incidents within the studies, however the proof will not be made publicly obtainable (video materials, medical data, and so on.) and inquiries for proof (calls, emails) have gone unanswered. Having acknowledged these struggles of verifiability and evaluation, each teams are generally thought-about to be credible, they usually have revealed congruent judgments of the conditions. They had been additionally issued 9 days aside and lined the talked about totally different areas, thereby making an emulation unlikely.

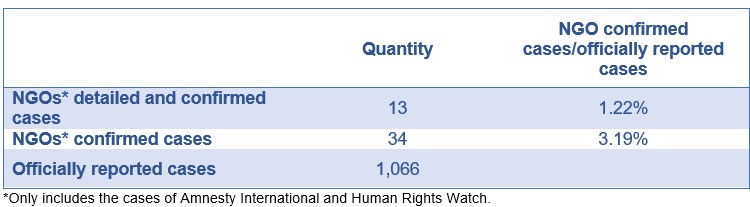

If we assume all knowledge introduced by the NGOs to be correct, the NGOs reported 14 detailed instances, and a further 20. In whole 34 instances are supplied, which suggests summarily each NGOs have accounted for 3.2% of the formally reported instances, or alternatively discovered 34 extra instances[5], which might heighten the overall variety of injured individuals to 1,100. Nevertheless, HRW abstains from describing 20 instances, and the detailed incidents which are introduced cowl little greater than 1%, diminishing its statistical relevance. Other than that, Amnesty Worldwide and HRW chosen the instances, thus making certain that probably the most extreme are reported (unsurprising, because the goal of a human rights organisation is to gather the breaches of human rights, not the adherence). Additionally they neglect to elaborate on the incidents they noticed the place police violence and brutality had been absent. With the idea of accuracy, this confirms that disproportionate violence was utilized by cops in a couple of instances, but it surely equally affirms the truth that it was taciturn for probably the most half.

Further concerns

To conclude all statistical concerns, two extra factors should be made: firstly, on the federal government statistics and secondly, on the trials after the 1-O.

The statistical proof introduced and defined rests upon official Catalan authorities numbers from the 1st of October 2018 (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018). Notably, they had been revealed a full 12 months after the occasion and included nervousness assaults in addition to individuals with single bruises – are these circumstances, or accidents that may be classed as police violence and even brutality? Each classes collectively make up for 47% of the accidents listed (Determine 5) and have been subjected to allegations of inflation (Iglesias, 2017). Nevertheless, these allegations should not solely levelled at one facet (ibid.; BBC, 2017c; The Premium Occasions, 2017) because the police harm depend additionally jumped from 39 to 431 in a single day[6]. However in distinction to the statistics revealed by the Catalan Well being Division, the nationwide authorities defined that the rise stems from the officers that obtained bruises, scratches, and bites (El País, 2017c).

The second comment issues the judicial proceedings towards police forces accused of police brutality. Most of them had been dismissed, both attributable to lack of identification of the person officer or as a result of adequate proof was lacking (The Native, 2019; García, 2019). Total, eight policemen had been formally investigated by a Spanish court docket, a microscopic determine in proportion to the police presence (The Native, 2019). Principally, nevertheless, the low variety of investigations will not be indicative of an absence of police brutality, but it surely underlines the argument of this work.

Conclusion: Police Brutality In opposition to Voters?

After the consideration of the introduced proof, we return to the preliminary analysis query:

Had been the accusations of police violence and brutality throughout the Catalan independence referendum 2017 justified, or did the state utilise official power throughout an unlawful public meeting? What are the broader implications?

By means of the statistical concerns of formally reported numbers, I’ve tried to reveal the discrepancy between the illustration of the state motion throughout the 1-O (medial and tutorial) and the official studies. This inconsistency derives from variations between the allegations of police violence and brutality and the low numbers of deployed cops, the low interference charge at polling stations (lower than 4%), the small variety of injured individuals in comparison with voters, and the comparatively low harm severity. As well as, the studies of the early withdrawal – albeit not formally verified – help the road of argument. The analysis of the NGO studies, that current counter-evidence to my evaluation, lacks statistical relevance (reported on 1-3.2% of instances) for an evaluation of widespread police brutality. Furthermore, the absence of verifiable proof, the imprecision of the descriptions, the reporting of solely extreme police power incidents, and the lacking whole variety of investigated incidents obscure the image additional.

In conclusion, there have been incidents of police violence and brutality, however the majority of the collisions between the state’s police forces and protesters resulted in none or few and predominantly minor accidents. What was revealed on social media, in conventional media, and the studies of the NGOs, due to this fact, reveals the experiences of a slightly restricted variety of individuals throughout 1-O, however has dominated public notion to an unwarranted diploma. This portrayal has led to a judgment of the proportionality of the police motion that’s contradictory to the official details and wishes rectification. This outcome, nevertheless, doesn’t justify police violence or brutality towards peaceable demonstrators, which is and stays reprehensible in addition to undeserving of a constitutional state, however reveals that from a purely quantitative standpoint there was hardly any police violence or brutality.

Moreover, and within the broader context of the Catalan-Spanish relations, these findings run counter to the final narrative. Sometimes, the Catalan minority presents itself or is depicted because the oppressed (Òmnium Cultural, 2017; La Opinión a Coruña, 2017; Renes, 2019; Guinjoan and Rodon, 2017; Rico, 2017; Síndic de Greuges de Catalunya, 2017; Síndic de Greuges de Catalunya, 2018). The media protection that adopted the referendum in 2017 proves this, with Òmnium Cultural (2017), politicians like Carles Puigdemont (Masó, 2020), and information shops (La Opinión a Coruña, 2017; Guinjoan and Rodon, 2017; Rico, 2017) portray Catalans as subjugated. On this story, the Spanish state is usually labelled as a ‘francoesque tyrant’ (BBC, 2019) or the oppressor (Miley and Garvía, 2019). The publicly circulated happenings of the referendum affirmed the depiction, however the right here introduced evaluation contradicts the standard image.

I’d due to this fact argue that the general public notion is flawed and has fallen prey to Catalan propaganda. Nonetheless, this doesn’t imply that the central authorities has not contributed to the angle of earlier and far more violent reactions to civil unrest. Moreover, one might argue that the dispatching of the Nationwide Police and Civil Guard will be understood as an try at oppression, and even when the interference was largely reasonable it was nonetheless authority enforcement by means of violence. Other than that, the refusal to barter after the referendum seemingly validated the tyrant label, even when the non-agreement was primarily based on an affordable precept, and due to this fact exacerbated the political impasse.

As is obvious from the historical past of Spanish-Catalan relations, regional independence has been a problem for the previous ten years and the 1-O was solely the newest pinnacle. There is no such thing as a resolution in sight, and a lot of the blame for the political deadlock will be positioned on the Spanish authorities – they’ve ignored the calls for for change since 2010. If the Spanish authorities desires to maintain Catalonia and the opposite areas with comparable aspirations as part of Spain, they must take into account elementary change, and enter negotiations. In any other case, as has been seen in historical past time and time once more, the difficulty has critical potential to show insurmountable. Eire, for instance, descended right into a warfare of independence when the British Empire refused to implement House Rule – leading to a continued battle on the island (Regan, 2007, pp. 197-223).

On the constructive facet, I consider the state of affairs between Madrid and Barcelona has not but reached irreversibility, particularly because the current COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the drive of the motion. Regional secessionism has misplaced its momentum for now, which gives a window of alternative. However with a purpose to produce an answer, the Spanish authorities wants to simply accept that ignoring the political calls for of Catalonia will yield no decision. A compromise must be reached and to this point, Catalonia has demonstrated the larger willingness, whereas Madrid continues to bury its head within the sand. The flames of the Catalan independence motion can flare up once more at any time, as seen after the incarceration of Pablo Hasél. The accusations of police brutality had been thus just one try in Catalonia’s historical past of incitement for independence help.

Notes

[1] On the time the President of the Catalan Generalitat (regional parliament) who led the events that organised the referendum.

[2] For extra data on Pablo Hasél please learn Congostrina, Bono and Carranco (2021).

[3] The referendum was thought-about invalid on a number of totally different grounds by worldwide observer missions. For additional data please see: El Plural, 2017; Worldwide Restricted Remark Mission, 2017; Colomé, 2017; Europa Press, 2017a; De Rabassa, 2017 and El País, 2017a.

[4] As talked about earlier (Footnote 3) because of the non-compliance of the administration with worldwide voting pointers electoral fraud was attainable, thereby additional diminishing the reliability of the quantity.

[5] Or something in between because it stays unclear if the NGO-recorded accidents are a part of the official statistics.

[6] The injured cops won’t be thought-about at this level as a result of it might transcend the scope of this work.

Appendix

Determine 1: Comparability of the voters to the voters and whole injured individuals

Sources: Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya, 2020; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 2: Abstract I of all formally reported injured individuals, Generalitat de Catalunya, 1st of October 2018

Sources: Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya, 2020; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 3: Abstract II of all formally injured individuals, Generalitat de Catalunya, 1st of October 2018

Sources: Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 4: Comparability of voters to injured individuals

Sources: Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017a; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 5: Complete abstract of the varieties of reported accidents, 2018

Sources: Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017b; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017c, Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 6: Abstract of the severity of reported accidents

Sources: Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018.

Determine 7: Comparability of police presence throughout the 1-O and El Clásico

Sources: BBC, 2017e; Lowe, 2019; March, 2018, pp. 72-86.

Determine 8: Abstract of police interferences at polling stations

Sources: El Plural, 2017; March, 2018, p. 88; Ministerio del Inside, 2017.

Determine 9: Abstract of the reported instances of the NGOs

Sources: Amnesty Worldwide, 2017c; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018; Human Rights Watch, 2017.

Bibliography

20 Minutos Editora (2017) ‘La Fiscalía se querella contra los miembros de la Sindicatura Electoral del referéndum’, 14th of September. Out there at: https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/3134789/0/fiscalia-querella-sindicatura-electoral-referendum/ (Accesssed: 03/10/2021).

ABC Cataluña (2017) ‘La mujer que aseguró que le habían roto los dedos de una mano cube ahora que solo tiene una inflamación’, third of October. Out there at: https://www.abc.es/espana/catalunya/abci-mujer-aseguro-habian-roto-dedos-mano-reconoce-ahora-solo-tiene-capsulitis-201710030845_noticia.html?ref=https:%2Fpercent2Fes.wikipedia.orgpercent2F (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Alandete, D., Dolz, P., and Busquets, J. (2017) ‘‘Hackers’ rusos ayudan a tener activa la net del referéndum’, in El País, twenty eighth of September. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2017/09/27/actualidad/1506539908_825347.html (Accessed: 03/09/2021).

Alberola, M. (2016) ‘El Rey no propone a ningún candidato y aboca a nuevas elecciones en junio’, in El País, twenty seventh of April. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2016/04/26/actualidad/1461689973_619104.html (Accessed: 06/10/2021).

Alpert, G. P. and Dunham, R. G. (2004) Understanding Police Use of Drive: Officers, Suspects, and Reciprocity. Cambridge: Cambridge College Press. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511499449.

Altimira, O. (2017) ‘”Que el referéndum sea ilegal no significa que se pueda combatir jurídicamente de cualquier manera”’, in El Diario, 14th of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/politica/referendum-ilegal-significa-combatir-cualquier_128_3191951.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Amnesty Worldwide (2015) Use of Drive – pointers for implementation of the UN primary rules on using power and firearms by regulation enforcement officers. Out there at: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/information/use_of_force.pdf (Accessed: 06/09/2021).

Amnesty Worldwide (2017a) 1-O: Las autoridades estatales y catalanas deben garantizar los derechos a la libertad de expresión, reunión y manifestación. Out there at: https://www.es.amnesty.org/en-que-estamos/noticias/noticia/articulo/1-o-las-autoridades-estatales-y-catalanas-deben-garantizar-los-derechos-a-la-libertad-de-expresion/ (Accessed: 03/09/2021).

Amnesty Worldwide (2017b) Spain: Extreme use of power by Nationwide Police and Civil Guard in Catalonia. Out there at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/newest/information/2017/10/spain-excessive-use-of-force-by-national-police-and-civil-guard-in-catalonia/ (Accessed: 06/10/2021).

Amnesty Worldwide (2017c) Spain: Latest developments in Catalonia from 1 October. Out there at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/paperwork/eur41/7473/2017/en/ (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

Arroyo, E. (2017) ‘La ‘operación Anubis’ desmonta el referéndum independentista en 20 horas’, in El Español, 21st of September. Out there at: https://www.elespanol.com/espana/politica/20170921/248475323_0.html (Accessed: 03/09/2021).

Asociación Professional Derechos Humanos de España (2017) Comunicados Ante el 1O. Out there at: https://apdhe.org/ante-el-1o/ (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

Bandera, E. (2017) ‘El Ayuntamiento de Gijón prohíbe una charla sobre Cataluña en un centro municipal’, in La Voz de Asturias, thirteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.lavozdeasturias.es/amp/noticia/gijon/2017/09/13/charla/00031505326965578184290.htm (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

BBC (2010) ‘Catalan protesters rally for larger autonomy in Spain’, 10th of July. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/10588494 (Accessed: 05/09/2021).

BBC (2015) ‘Catalonia vote: pro-independence events win elections’, 28th of September. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/world-europe-34372548 (Accessed: 05/09/2021).

BBC (2017a) ‘Catalonia referendum: Violence as police block voting’, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/av/world-europe-41463955 (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

BBC (2017b) ‘Catalonia: Video reveals violence as police tackles voters’, 1st of October. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/av/world-europe-41459692 (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

BBC (2017c) ‘Did voters face worst police violence ever seen within the EU?’, 27th of October. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/world-europe-41677911 (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

BBC (2017d) ‘Cataluña: el presidente Puigdemont firma una declaración de independencia y suspende sus efectos para promover el diálogo con España’, tenth of October. Out there at: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-internacional-41573407 (Accessed: 16/10/2021).

BBC (2017e) ‘Catalonia referendum: Madrid strikes to take over native policing’, twenty third of September. Out there at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/world-europe-41373977 (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

BBC (2019) ‘Catalonia’s bid for independence from Spain defined’, 18th of October. Availabe at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/information/world-europe-29478415 (Accessed: 15/10/2021).

Beltrán de Felipe, M. (2019) ‘Myths and Realities of Secessionisms’. Out there at: https://hyperlink.springer.com/guide/10.1007percent2F978-3-030-11632-3 (Accessed: 24/09/2021).

Bernat, I. and Whyte, D. (2020) ‘Postfascism in Spain: The Wrestle for Catalonia’, in Crucial Sociology, 46(4–5), pp. 761–776. DOI: 10.1177/0896920519867132.

Berwick, A. and Cobos, T. (2016) ‘Catalonia to carry independence referendum with or with out Spain’s consent’, in Reuters, 28th of September. Out there at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-spain-catalonia-idUSKCN11Y2FR (Accessed: 05/10/2021).

Berwick, A. and Dowsett, S. (2017) ‘Demoralized and divided: inside Catalonia’s police power’, in Reuters, 24th of October. Out there at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-spain-politics-catalonia-mossos-analy-idUSKBN1CT2MT (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

Birke, B. and Kellner, H.-G. (2017) ‘Die Unabhängigkeit als Traum’, in Deutsche Welle, 30th of October. Out there at: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/katalonien-die-unabhaengigkeit-als-traum.724.de.html?dram:article_id=399481 (Accessed: 04/10/2021).

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2010) Suplemento TRIBUNAL CONSTITUCIONAL. Out there at: https://boe.es/boe/dias/2010/07/16/pdfs/BOE-A-2010-11409.pdf (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2017a) I. DISPOSICIONES GENERALES: MINISTERIO DE LA PRESIDENCIA Y PARA LAS ADMINISTRACIONES TERRITORIALES. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2017/10/27/pdfs/BOE-A-2017-12328.pdf (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2017b) I. DISPOSICIONES GENERALES: CORTES GENERALES. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/res/2017/10/27/(1)/dof/spa/pdf (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2017c) I. DISPOSICIONES GENERALES: PRESIDENCIA DEL GOBIERNO. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2017/10/28/pdfs/BOE-A-2017-12330.pdf (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Burgen, S. and Jones, S. (2019) ‘Violent clashes over Catalan separatist leaders’ jail phrases’, in The Guardian, 14th of October. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/14/catalan-separatist-leaders-given-lengthy-prison-sentences (Accessed: 19/09/2021).

Castro, I. and Ponce de Léon, R. (2017) ‘Rajoy cesa al Govern, disuelve el Parlament y convoca elecciones para el 21 de diciembre’, in El Diario, twenty seventh of October. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/rajoy-cesa-puigdemont-govern_1_3099615.html (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Cetrà, D. (2019) Nationalism, Liberalism and Language in Catalonia and Flanders. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

CNN (2010) ‘Greater than 1 million protest court docket ruling in Barcelona’, 10th of July. Out there at: https://version.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/07/11/spain.protests/index.html (Accessed: 05/10/2021).

Colomé, J. (2017) ‘La misión de observadores concluye que el referéndum no cumple los “estándares internacionales”’, in El País, third of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2017/10/03/actualidad/1507046129_416345.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (2001) The European Code of Police Ethics. Out there at: https://polis.osce.org/european-code-police-ethics (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Confilegal (2017) ‘23 juzgados de Cataluña investigan denuncias por los incidentes del 1-O’, eighth of October. Out there at: https://confilegal.com/20171008-23-juzgados-de-cataluna-investigan-denuncias-por-los-incidentes-del-1-o/ (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

Congostrina, A. (2017) ‘La Generalitat cifra en 844 los atendidos por heridas y ataques de ansiedad’, in El País, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2017/10/01/catalunya/1506820036_546150.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Congostrina, A., Bono, F., and Carranco, R. (2021) ‘Catalonia rocked by third night time of protests over jailing of rapper Pablo Hasél’, in El País, nineteenth of February. Out there at: https://english.elpais.com/society/2021-02-19/catalonia-rocked-by-third-night-of-protests-over-jailing-of-rapper-pablo-hasel.html (Accessed: 24/09/2021).

Cortizo, G. (2017a) ‘El Tribunal Constitucional suspende la ley que regula el referéndum’, in El Diario, seventh of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/tribunal-constitucional-suspende-permite-referendum_1_3205080.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Cortizo, G. (2017b) ‘Sectores de la política y la judicatura, alarmados ante la amenaza de detención contra 712 alcaldes’, in El Diario, thirteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/sectores-politica-judicatura-alarmados-detencion_1_3192036.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Council of Europe (2017) Commissioner calls on Spain to analyze allegations of disproportionate use of police power in Catalonia. Out there at: https://www.coe.int/en/net/commissioner/-/commissioner-calls-on-spain-to-investigate-allegations-of-disproportionate-use-of-police-force-in-catalonia (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Council of the European Union (2012) Compendium of rules for using power and consequent steering for the difficulty of guidelines of engagement (ROE) for cops taking part in EU disaster administration operations. Out there at: https://www.statewatch.org/media/paperwork/information/2012/oct/eu-council-crisis-management-12415-rev6-02.pdf (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

De Rabassa, R. (2017) ‘El Govern incumple (también) su propia ley’, in El País: Cinco Días, seventeenth of October. Out there at: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2017/10/16/mercados/1508171125_573561.html (Accessed: 08/10/2021).

Deutsche Welle (2016a) ‘Catalonia approves independence referendum’, 7th of October. Out there at: https://www.dw.com/en/catalonia-approves-independence-referendum/a-35985408 (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

Deutsche Welle (2016b) ‘Catalan chief pledges ‘binding’ independence referendum in 2017’, 31st of December. Out there at: https://www.dw.com/en/catalan-chief-pledges-binding-independence-referendum-in-2017/a-36959215 (Accessed: 23/09/2021).

Deutsche Welle (2017a) ‘+++ Catalan independence vote: Dwell updates +++’, 1st of October. Out there at: https://www.dw.com/en/catalan-independence-vote-live-updates/a-40750567 (Accessed: 16/10/2021).

Deutsche Welle (2017b) ‘Catalonia referendum violence prompts European response’, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://www.dw.com/en/catalonia-referendum-violence-prompts-european-reaction/a-40772750 (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2017a) LEY 19/2017, de 6 de septiembre, del referèndum de autodeterminación. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/ccaa/dogc/2017/7449/f00001-00012.pdf (Accessed: 08/10/2021).

Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2017b) DECRETO 140/2017, de 6 de septiembre, de normes complementarias para la realización del Referéndum de Autodeterminación de Cataluña. Out there at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1oBg3T5oVooqDJo7eD-BFjrFmUEuW-U6n/view?usp=sharing (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Díez, A. and Mateo, J. (2017) ‘El Gobierno aplica el artículo 155 para destituir a Puigdemont y sus consejeros’, in El País, 21st of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2017/10/21/actualidad/1508572466_221699.html (Accessed: 16/10/2021).

El Confidencial (2017) ‘La Guardia Civil interviene más de 1.300.000 carteles y materials de propaganda del 1-O’, seventeenth of September. Out there at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/cataluna/2017-09-17/guardia-civil-requisa-material-1-0-montcada_1444876/ (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

El Diario (2017a) ‘La Fiscalía pide cerrar webs del referéndum y fianzas para miembros del Govern’, eighth of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/fiscalia-referendum-fianzas-miembros-govern_1_3204438.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

El Diario (2017b) ‘La Guardia Civil detiene al número dos de Junqueras y a otras 13 personas en una operación contra el 1-O’, twentieth of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/guardia-civil-conselleria-economia-catalunya_1_5865836.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

El Diario (2017c) ‘La prensa internacional lleva a sus portadas las cargas policiales en Catalunya’, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/rastreador/prensa-internacional-portadas-policiales-catalunya_132_3151921.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

El Mundo (2017) ‘La Guardia Civil registra la imprenta de Constantí en busca de materials de papelería para el 1-O’, 8th of September. Out there at: https://www.elmundo.es/cataluna/2017/09/08/59b29623268e3eba478b47f8.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

El Nacional (2017) ‘La Guardia Civil investiga una imprenta en Sant Feliu de Llobregat’, 14th of September. Out there at: https://www.elnacional.cat/es/politica/guardia-civil-imprenta-sant-feliu-llobregat_191568_102.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

El País (2017a) ‘¿Cumple con alguna garantía básica este referéndum?’, 1st of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/10/01/hechos/1506847430_088864.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

El País (2017b) ‘¿Cuántos heridos hubo en realidad el 1-O?’, 3rd of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/10/02/hechos/1506963876_226068.html (Accessed: 26/09/2021).

El Plural (2017) ‘Gana la abstención: el 58% de los catalanes no votó’, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://www.elplural.com/politica/gana-la-abstencion-el-58-de-los-catalanes-no-voto_110674102 (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

Eldridge, A. (2021) ‘Mariano Rajoy’, in Encyclopedia Britannica, 23rd of March. Out there at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mariano-Rajoy (Accessed: 01/04/2021).

Europa Press (2017a) ‘Los observadores concluyen que el referéndum no pudo cumplir los estándares internacionales’, 3rd of October. Out there at: https://www.europapress.es/catalunya/noticia-observadores-concluyen-referendum-no-pudo-cumplir-estandares-internacionales-20171003193715.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Europa Press (2017b) ‘Maza ordena a Mossos, Guardia Civil y Policía intervenir las urnas y otros efectos para evitar el referéndum’, eighth of September. Out there at: https://www.europapress.es/nacional/noticia-maza-ordena-mossos-guardia-civil-policia-intervenir-urnas-evitar-referendum-20170908142401.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Discipline, B. (2015) ‘The evolution of sub-state nationalist events as state-wide parliamentary actors, CiU and PNV in Spain’, in Gillespie, R. (ed.) Contesting Spain? The dynamics of nationalist actions in Catalonia and the Basque Nation. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 116-136.

Buddy, J. W. (2012) Stateless nations: Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Previous Nations. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gálvez, J. (2017) ‘Reporteros Sin Fronteras compara la presión a los medios en Cataluña con las “campañas de Trump”’, in El País, thirteenth of October. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2017/10/13/actualidad/1507896040_208112.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

Garcia Valdivia, A. (2019) ‘Catalan Separatist Leaders Sentenced To 9-13 Years Jail Over 2017 Independence Referendum’, in Forbes Journal, 15th of October. Out there at: https://www.forbes.com/websites/anagarciavaldivia/2019/10/15/catalan-separatist-leaders-sentenced-to-9-13-years-prison-over-independence-referendum-in-2017/?sh=606835fc579e (Accessed: 19/09/2021).

García, C. (2016) ‘Utilizing road protests and nationwide commemorations for nation-building functions: the marketing campaign for the independence of Catalonia (2012-2014)’, in Journal of Worldwide Communication, 22(2), pp. 229–252. DOI: 10.1080/13216597.2016.1224195.

García, J. (2019) ‘Exceso o mesura: juicio a los policías del 1-O’, in El País, 14th of March. Out there at: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2019/03/18/catalunya/1552939129_099457.html (Accessed: 20/09/2021).

Garea, F. (2017) ‘La Generalitat incumple al menos 20 artículos de su propia ley de referéndum’, in El Confidencial, 1st of October. Out there at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/2017-10-01/generalitat-incumple-20-articulos-propia-ley-referendum_1453126/ (08/10/2021).

Generalitat de Catalunya (2017a) REFERÈNDUM D’AUTODETERMINACIÓ DE CATALUNYA, Resultats definitius. Out there at: http://estaticos.elperiodico.com/sources/pdf/4/3/1507302086634.pdf (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

Generalitat de Catalunya (2017b) Actualització del Departament de Salut en relació a les persones que han rebut assistència sanitària durant el referèndum (21:30h). Out there at: https://govern.cat/gov/notes-premsa/303465/actualitzacio-del-departament-salut-relacio-persones-que-han-rebut-assistencia-sanitaria-durant-referendum-2130h (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

Generalitat de Catalunya (2017c) Primer d’octubre, informe d’una repressió. Out there at: https://govern.cat/govern/docs/2018/10/04/15/48/c1ddabd0-fbdf-4a92-ae64-66ada9cf925f.pdf (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

Generalitat de Catalunya (2018) Primer d’Octubre. Out there at: b3d8c567-b566-49a6-9b0e-8fb75002ea21.pdf (govern.cat) (Accessed: 14/10/2021).

Gobierno de España (2016) Constitución Española. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/codigos/codigo.php?id=158_Constitucion_Espanola_________________The_Spanish_Constitution_&modo=1 (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Gobierno de España (2017) Rajoy: “Hoy ha prevalecido la democracia porque se ha cumplido la Constitución”. Out there at: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/presidente/actividades/Paginas/2017/011017referendum1o.aspx (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

Gobierno de España (2021a) Código de la Policía Nacional. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/legislacion/codigos/codigo.php?id=18&modo=1¬a=0 (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Gobierno de España (2021b) Código de la Guardia Civil. Out there at: https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/codigos/codigo.php?id=007_Codigo_de_la_Guardia_Civil&modo=1 (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Goff, P., et al. (2016) THE SCIENCE OF JUSTICE: RACE, ARRESTS, AND POLICE USE OF FORCE. The Heart for Policing Fairness. Out there at: https://policingequity.org/photographs/pdfs-doc/CPE_SoJ_Race-Arrests-UoF_2016-07-08-1130.pdf (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Greenfield, P., Russell, G., and Slawson, N. (2017) ‘Catalonia referendum: 90% voted for independence, say officers – because it occurred’, in The Guardian, 26th of October. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/dwell/2017/oct/01/catalan-independence-referendum-spain-catalonia-vote-live (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

Güell, O. (2017) ‘Poll bins: Catalonia’s best-kept secret’, in El País, 3rd of October. Out there at: https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2017/10/03/inenglish/1507025882_591932.html (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

Guinjoan, M. and Rodon, T. (2017) ‘What standards did the Spanish police use to repress in particular municipalities?’, in NacióLleida, 15th of October. Out there at: https://www.naciodigital.cat/lleida/noticia/25630/quin/criteri/va/fer/servir/policia/espanyola/reprimir/municipis/concrets (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Heller, F. (2015) ‘Catalan separatists ship shudders by means of Madrid’, in EURACTIV Spain, 22nd of July. Out there at: https://www.euractiv.com/part/elections/information/catalan-separatists-send-shudders-through-madrid/ (Accessed: 05/10/2021).

Human Rights Watch (2017) Spain: Police Used Extreme Drive In Catalonia. Human Rights Watch Web site. Out there at: https://www.hrw.org/information/2017/10/12/spain-police-used-excessive-force-catalonia (Accessed: 11/10/2021).

Iglesias, L. (2017) ‘”Contamos como agresiones hasta las ansiedades por ver las cargas por televisión”’, in El Mundo, ninth of October. Out there at: https://www.elmundo.es/cronica/2017/10/08/59d9237646163f58078b45c2.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (2020) Població a 1 de gener. Províncies. Out there at: http://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=aec&n=245 (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

Worldwide Restricted Remark Mission (2017) Preliminary Assertion, 3 October 2017 – Barcelona, Spain. Out there at: https://static1.ara.cat/ara/public/content material/file/authentic/2017/1005/20/informe-preliminar-de-la-missio-internacional-coordinada-per-daan-everts-bacc584.pdf (Accessed: 11/09/2021).

Jones, S. (2016) ‘Mariano Rajoy sworn in as Spain’s PM after impasse damaged’, in The Guardian, 31st of October. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/31/mariono-rajoy-to-be-sworn-in-as-spains-prime-minister (Accessed: 08/10/2021).

Jones, S. (2017a) ‘Catalonia calls independence referendum for October’, in The Guardian, 9th of June. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/09/catalonia-calls-independence-referendum-for-october-spain (Accessed: 08/10/2021).

Jones, S. (2017b) ‘Catalan president Carles Puigdemont ignores Madrid’s ultimatum’, in The Guardian, sixteenth of October. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/16/catalan-president-carles-puigdemont-ignores-madrids-ultimatum (Accessed: 16/10/2021).

Julve, R. (2015) ‘JxSí y la CUP registran en el Parlament la declaración de “inicio del proceso” hacia la independencia’, in Política, twenty eighth of October. Out there at: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/20151027/declaracion-inicio-proceso-independencia-cup-junts-pel-si-4621507 (Accessed: 05/09/2021).

Keely, G. (2019) ‘Catalan independence protests kick off at El Clasico match’, in Al Jazeera, 19th of December. Out there at: https://www.aljazeera.com/sports activities/2019/12/19/catalan-independence-protests-kick-off-at-el-clasico-match (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

La Opinión a Coruña (2017) ‘Inside busca en A Coruña las urnas del referéndum de Cataluña’, thirteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.laopinioncoruna.es/coruna/2017/09/13/interior-busca-coruna-urnas-referendum-24203640.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

La Vanguardia (2017a) ‘‘El Punt Avui’, ‘Vilaweb’, ‘Nació Digital’ y ‘El Nacional’ reciben la notificación de la Guardia Civil’, fifteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20170915/431299384016/el-punt-avui-vilaweb-reciben-notificacion-guardia-civil.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

La Vanguardia (2017b) ‘Martín Pallín, fiscal y magistrado emérito del TS: “Las querellas son forzadas y no ajustadas a la legalidad”’, sixteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20170916/431321620834/martin-pallin-querellas-referendum-1-o-forzadas.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

La Vanguardia (2017c) ‘Reacciones internacionales a las cargas policiales en el 1-O’, 1st of October. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/internacional/20171001/431696016973/charles-michel-belgica-corbyn-violencia-dialogo-europa.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

La Vanguardia (2017d) ‘Inside asegura que 431 policías y guardias civiles resultaron heridos en el dispositivo del 1-O’, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20171002/431755741107/interior-policias-guaridas-civiles-heridos-1-o.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

La Vanguardia (2017e) ‘Vídeo y texto íntegros de la comparecencia de Puigdemont ante el Parlament’, 10th of October. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20171010/431967857427/discurso-puigdemont-parlament-10o.html (Accessed: 16/10/2021).

Lawrence, R. G. (2000) The Politics of Drive Media and the Building of Police Brutality. Berkeley: College of California Press.

Letamendia, A. (2018) ‘MOBILIZATION, REPRESSION AND BALLOT: TRACING THE KEY ELEMENTS OF THE SELF-DETERMINATION REFERENDUM ON OCTOBER 1, 2017 IN CATALONIA’, in Social Battle Yearbook, 7(7). DOI: 10.1344/ACS2018.7.1.

Libertad Digital (2017) ‘El juez que investiga la actuación policial del 1-O baja el número de heridos a 130’, sixth of October. Out there at: https://www.libertaddigital.com/espana/2017-10-06/el-juez-que-investiga-la-actuacion-policial-del-1-o-baja-el-numero-de-heridos-a-130-1276607126/ (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

López-Fonseca, Ó. (2017a) ‘Riot police operations known as off early after outcry over violence in Catalonia’, in El País, 2nd of October. Out there at: https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2017/10/02/inenglish/1506943672_303303.html (Accessed: 09/10/2021).

López-Fonseca, Ó. (2017b) ‘El Govern rechaza que la Guardia Civil mande sobre los Mossos’, in El País, 23rd of September. Out there at: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2017/09/23/catalunya/1506161064_662386.html (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

López-Fonseca, Ó. (2020) ‘Inside aumenta en 3.800 el número de policías y guardias civiles en dos años’, in El País, seventh of March. Out there at: https://elpais.com/espana/2020-03-07/interior-aumenta-en-3800-el-numero-de-policias-y-guardias-civiles-en-dos-anos.html (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Lowe, S. (2019) ‘Security is the purpose for this clásico as police collect amid political unrest’, in The Guardian, 17th of December. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/soccer/2019/dec/17/safety-is-the-goal-for-this-clasico-as-police-gather-amid-political-unrest (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

March, Oriol (2018). Los entresijos del ‘procés’. Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata.

Marín, H. (2017) ‘La Guardia Civil requisa 100.000 carteles de propaganda del 1-O en una imprenta de Barcelona’, in El Mundo, fifteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.elmundo.es/cataluna/2017/09/15/59bbd15e22601dc1478b45ee.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Marraco, M. (2017) ‘La Fiscalía se querella contra Puigdemont y el Govern y ordenará a Mossos, Policía, Guardia Civil intervenir las urnas’, in El Mundo, seventh of September. Out there at: https://www.elmundo.es/espana/2017/09/07/59b12946ca4741e30c8b463b.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Martí, D. and Cetrà, D. (2016) ‘The 2015 Catalan election: a de facto referendum on independence?’, in Regional & Federal Research, 26(1), pp. 107–119. DOI: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1145116.

Masó, P. (2020) ‘Catalan presidents Mas, Puigdemont and Torra be a part of to denounce Spain’s repression’, in El Nacional, 9th of October. Out there at: https://www.elnacional.cat/en/politics/mas-puigdemont-torra-catalan-presidents-perpinya_545751_102.html (Accessed: 15/09/2021).

Miley, T. J. and Garvía, R. (2019) ‘Battle in Catalonia: A Sociological Approximation’, in Family tree, 3(4), pp. 56-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040056.

Minder, R. (2017a) ‘Catalan Police Face Their Personal Take a look at of Independence’, in The New York Occasions, 30th of September. Out there at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/30/world/europe/catalonia-police-independence.html (Accessed: 31/09/2021).

Minder, R. (2017b) ‘Spain Asks Catalonia: Did You Declare Independence or Not?’, in The New York Occasions, 11th of October. Out there at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/world/europe/catalonia-spain-independence-mariano-rajoy.html (Accessed: 16/09/2021).

Minder, R. and Barry, A. (2017) ‘Catalonia’s Independence Vote Descends Into Chaos and Clashes’, in The New York Occasions, 1st of October. Out there at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/01/world/europe/catalonia-independence-referendum.html (Accessed: 11/09/2021).

Ministerio del Inside (2009) Código Normativo de Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad del Estado. Out there at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NF8ZmpncU1lNyjuaJ6FXr3wc3BunLrrn/view?usp=sharing (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Ministerio del Inside (2017) A las 17:00 horas son ya 92 los colegios electorales cerrados por Policía Nacional y Guardia Civil en toda Cataluña. Out there at: http://www.inside.gob.es/noticias/detalle/-/journal_content/56_INSTANCE_1YSSI3xiWuPH/10180/7820088/ (Accessed: 10/10/2021).

Mossos d’Esquadra (2021) Tricentenari. Out there at: https://mossos.gencat.cat/ca/tricentenari/ (Accessed: 22/09/2021).

Navarro, M. (2017) ‘La Fiscalía ordena a los Mossos, la Policía Nacional y la Guardia Civil que requisen urnas’, in La Vanguardia, twelfth of September. Out there at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20170912/431225078354/fiscalia-ordena-mossos-policia-guardia-civil-requisar-urnas-referendum.html (Accessed: 02/10/2021).

Noguer, M. (2015) ‘Catalan parliament passes movement declaring begin of secession course of’, in El País, ninth of November. Out there at: https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2015/11/09/inenglish/1447067955_007589.html (Accessed: 05/10/2021).

Òmnium Cultural (2017) ‘Assist Catalonia. Save Europe.’ 16th of December. Out there at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wouNL14tAks (Accessed: 11/09/2021).

Parera, B. (2017) ‘La Fiscalía pide que Puigdemont y sus ‘consellers’ paguen fianza’, in El Confidencial, eighth of September. Out there at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/2017-09-08/la-fiscalia-pide-cerrar-las-webs-del-referendum-y-que-puigdemont-depositen-fianza_1440735/ (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Parlament de Catalunya (2017) Declaració dels representants de Catalunya. Out there at: https://www.parlament.cat/doc/intrade/238023 (Accessed: 17/10/2021).

Pérez, F. (2017) ‘El Constitucional suspende de urgencia la ley del referéndum’, in El País, eighth of September. Out there at: https://elpais.com/politica/2017/09/07/actualidad/1504781825_809788.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Preston, P. (2017) ‘Violence in Catalonia wanted nearer scrutiny in age of pretend information’, in The Guardian, 8th of October. Out there at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/08/catalonia-demo-injuries-fact-checking (Accessed: 01/10/2021).

Público (2017) ‘La Guardia Civil requisa las planchas para imprimir los carteles del referéndum’, sixteenth of September. Out there at: https://www.publico.es/politica/referendum-1-guardia-civil-requisa-planchas-imprimir-carteles-referendum.html (Accessed: 03/10/2021).

Puente, A. (2017a) ‘El Govern proclama los resultados del referéndum saltándose la ley aprobada en el Parlament’, in El Diario, sixth of October. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/politica/govern-resultados-referendum-saltandose-parlament_1_3146133.html (Accessed: 08/10/2021).

Puente, A. (2017b) ‘El Parlament aprueba la ley para declarar la independencia tras el 1-O’, in El Diario, eighth of September. Out there at: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/politica/parlament-catalunya-aprueba-declarar-independencia_1_3202800.html (Accessed: 08/03/2021).